“Stumbling” onto science in visual merchandising

by Peter Hamer

august, 2022

First things first, how do you know whether a display will be profitable or not?

Take some time to answer.

How much of your answer is based on emotion? Am I wrong if I say your answer is “a lot”? Now, what if I tell you there’s a different mindset, are you curious?

In recent years we’ve put so much weight on the profitability of displays based on emotional decisions that we’re now at the point where we don’t know if a display is an investment or a cost. Well, I discovered a display is always an investment if its origin is science-based.

Let me tell you why.

The need to think differently, I think

I came upon the notion of science in Visual Merchandising (VM) accidentally. During my corporate experiences at iconic brands, I became aware that VM was seen as one of the main business drivers at retail but I was always stunned at how much emotion played a role in deciding the final display. It was as if VM was the tool in charge of the final space AND brand coherence. From product unavailability to store design problems, there was nothing VM couldn’t fix. And in the back of my head, I wondered: if VM fixes things, that means something is broken. But was that really the case, or was this the true essence of VM?

To answer this, I switched to engineer mode and set out to prove whether that was the case, or not. The next step was to resign from my corporate role and embark on a solitary mission of discovery.

This mission started in January 2015 and in November 2016 i founded i see windows. A platform for me to share the scientific knowledge of VM. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves, I still need to tell you about that different mindset.

To see things differently, you must learn to see things with a different mindset.

The confusingly right path

I became a VM in 2011 by accident. As a matter of fact, my career in VM was one of the “let’s learn by doing” kinds of situations that turned out better than expected. I confess it was a challenge to move from product merchandising to VM, but I have absolutely no regrets.

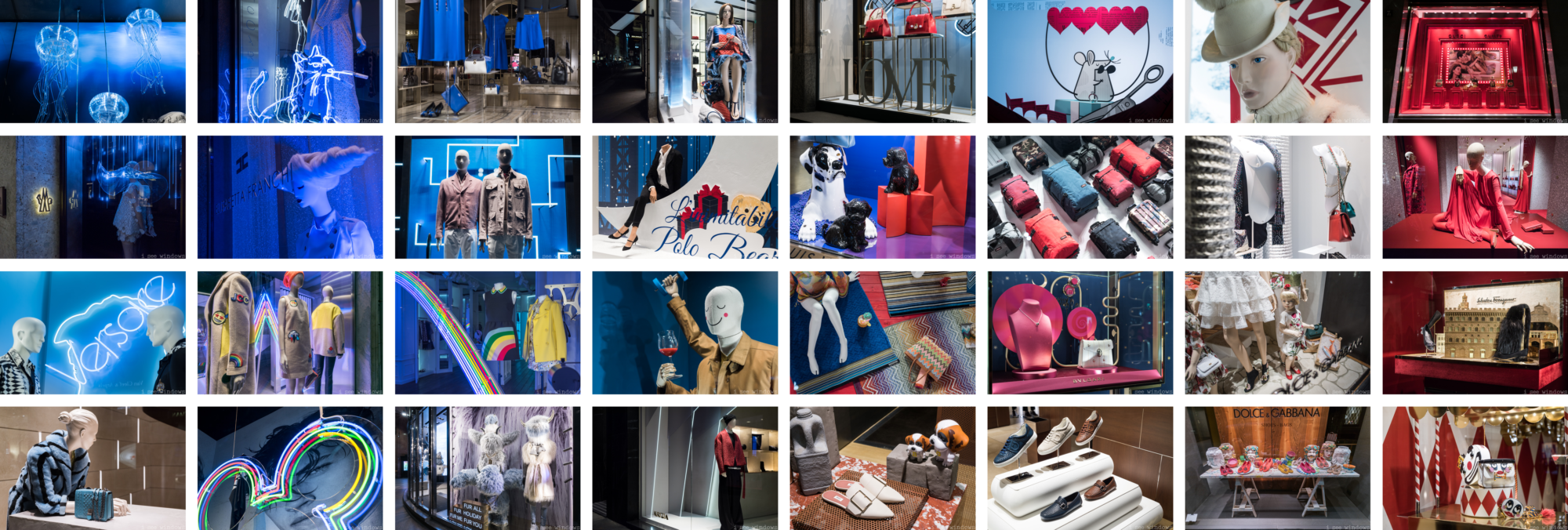

Since I had no academic background in the subject, I decided to face VM when it’s most vulnerable: at retail and at night. At night? Yes. You see I made it a habit to roam the city of Milan at night to look at and photograph all the displays. I did this because I wanted to learn first-hand from the “silent seller” and did so by documenting every display I felt told me something (positive or negative). In all honesty, I also photographed the ones that didn’t make me feel anything at all.

Now, taking photos came naturally to me, both my parents were amateur photographers (dad Hasselblad, mom Nikon), but taking photos of displays was different because the conditions just weren’t what I was used to. Why is this relevant you ask? Because this was the first time I had to look at displays differently, and in my case, through the lens of Leica. This weekly night habit led me to have 15,000+ photos of displays when I started my mission in 2015, and I knew these photos held an important piece of the answer I was looking for.

I approached this mission from an academic point of view with explanatory research. I developed hypotheses and followed a qualitative research structure where the photos became my primary source of data. This was accompanied by interviews, case studies, text analysis, and all the other things one would do whilst writing a thesis, a process that I’m sure my students will identify with.

The next step was to identify common denominators in the form of tags. In the beginning, all these tags were related to the design of the display. I looked at the use of color, the occasion of use, and the number of mannequins and products on display. This helped me create clusters but every time I thought I had found the right clusters; a new display would come along and prove me wrong. I realized then that I was too emotionally involved. I was analyzing displays with a creative mindset, but this brought no result. I had too many tags which were too granular to find a common language. A little frustrating.

This brought me to tackle the same problem from a different angle. First, by understanding the different fields related to retail. This included psychology (culture, consumer behavior, consumption and habits, and neuroscience), human factors and ergonomics (UI and UX, as well as the human eye), and the design process itself (UCD, manufacturing and materials, and circularity). With this under my belt, I realized I had to think differently to create a body of knowledge that was systematically organized. And thus, the idea of VM science was born.

Stumbling onto the Taxonomy of Displays

I continued the research with an in-depth study of 10 different brands selected on the availability of annual reports and/or financial statements, as well as the physical presence of retail in Milan. I needed to understand how the brand strategy was reflected in retail, especially in displays. What came from this analysis were four different factors that were present in various degrees in every single display across all brands. These factors were related to the brand’s verbal and non-verbal codes, communication and product presentation, the design of the store itself, and the product. Using these factors, it became easy to classify any display in a organized way.

Next was a classification of all the displays in my database that resulted in the development of the world’s first taxonomy of displays. This scheme was tried and tested with a focus group where participants demonstrated the ability to successfully classify a random selection of displays from different industries and cultures with the taxonomy. A personal and professional breakthrough moment!

To put science into practice, I used the taxonomy of displays as the foundation for the development of a design framework that I called the i1 Model. A framework that bridges business (strategy) and emotion (creativity).

A new mindset: stop making emotional displays

When we look at displays, we’re often emotionally triggered. This is fine if you’re shopping, but not if you’re in charge of developing the retail strategy. Emotional decisions are linked to wrongfully spending valuable resources and materials that bring frustration. Emotional decisions can also be linked to great success, but this trial-and-error approach is outdated in the competitive arena we’ve created in retail. We cannot rely on emotion to make a choice; we need to be scientific.

While this change of mindset may sound alienating, it’s not. Let’s define the use of science from both perspectives involved in display design:

STRATEGIC: A scientific mindset allows your displays to be as strategic as possible within a delimited creative context.

CREATIVE: A scientific mindset allows your displays to be as creative as possible within a delimited context led by business decisions.

In other words, the scope of this science is simply knowing which factors to leverage in the display. If there are no factors related to corporate investments, you’re creating a display that relies on creativity -> emotion. Trial-and-error.

On the other hand, a display that only includes factors related to corporate investments relies on the investment -> strategy. Cost intensive.

Display science is the invitation to create strategically emotional displays. The display should always be creative for the consumer but should be scientific for management. I’m a firm believer that retail is the place where you can understand how business is run. In your case, is it emotional? Strategic? Scientific? Or…

Get in touch

To learn more about visual merchandising science and how the i1 Model can help you focus your mindset to create scientific displays, send me a message or follow me on LinkedIn and Instagram.

related content

retail thoughts

august, 2022